I advocate on behalf and work in the addiction treatment industry. I do this despite that fact that very few programs are any good and most are horrendous. This is true for both in-patient and out-patient programs. They dress themselves up with fancy websites, glossy brochures, and friendly marketers. Back in the late 90s when I was a private first class (PFC) in the Army, Master Sergeant Spadoni occasionally told me that “You can’t polish a turd.”

I repeated this to one of my Rutgers students a half dozen years ago and he responded with, “Yeah, but you can roll it in glitter.” That is an apt description of the four most common marketing methods employed by treatment programs:

- They have many photographs (maybe even videos) of their glimmering facilities.

- They describe the extras they offer: gym memberships, yoga, equine therapy, whirl pools, sauna, music studios, and other shiny add-ons that sound impressive. Most of these offerings have little to no research to justify their presence in a treatment program but are there to jack up the costs (I’m pro-exercise, a huge fan of yoga, and can see the benefits of equine therapy, but they are just glitter if the clinical program isn’t solid).

- They offer a heart-warming story about a successful client and/or provide quotes from happy parents and patients.

- The owner or one of the head counselors or the marketer is in recovery, and they lead with that information to show that they “really understand” and “really care” and that this “isn’t about money.”

Over the last four years, I’ve written or edited a number of pieces that addressed a variety of the problems in the addiction treatment industry. You don’t need to read these to grasp the point of this article, but it will give you a much deeper understanding about my complaints.

- Frank Jones and I wrote a piece about how insurance companies deny coverage to pay for treatment and how the industry uses it as an excuse to act badly.

- Very few centers have a rigorous family program with a multi-family group. I’ve written about what multi-familly groups are and some basic advice for parents of young adults.

- Andrew Walsh investigated the 1-800 numbers and the conman tactics that treatment programs use to lure clients. Mr. Walsh detailed how much attention he got with good insurance and how they quickly got off the phone if he didn’t.

- Mr. Walsh wrote a piece about the lack of treatment beds for Medicaid patients. Substance abuse facilities are not interested in them. As a result, your chances of getting treatment depends upon your finances. It’s a true modern day civil rights issue.

- The Florida model is the industry’s end-around move to get insurance to pay for seeming residential care when they reject it. The companies house clients a few blocks or miles from an intensive outpatient program (IOP) and shuttle them back and forth. In theory, it is a decent idea. The major problem is that the housing is not licensed or regulated. The staff often suffers from a lack of experience, education, training and supervision. I wrote a basic plan to address this.

- Treatment centers brag about their CARF and Joint Commission certifications. These are non-government agencies that rate programs. Even terrible ones can get their approval, which makes the whole rating system virtually worthless.

Treatment program owners, directors, and marketers often call me or email me or try to connect with me on LinkedIn. I tell them I don’t really have clients to send them and that I am highly critical of the treatment industry. They respond that they have high standards too and push for meetings. Over the last few months, I’ve held court at Rutgers and had a number of colleagues and supervisees attend those meetings. We ask them a grueling set of questions and every single program has come up sorely lacking. Here are the three most important questions that you should ask:

- Are all the therapists and workers supervised? How often do they get supervised? By whom? What are the supervisor’s credentials? What proof do you have of the supervisor’s expertise?

- How much individual therapy do the patients get?

- What data do you have to show the effectiveness of your program? Is it internally collected or do you have a neutral outsider do it? What metrics do you have to show how soon patients get a physical, visit the dentist and see a gynecologist? Do you measure stable housing and reduced involvement in the criminal justice system? What is the percentage that you help enroll in GED or vocational training or college courses? How many clients are set up in aftercare? How do you vet those aftercare programs?

Here is why those questions are important:

- Substance abuse and mental health counseling are difficult to master and are quite draining. Staff needs to be well trained and supervised at least one hour a week (two hours is my base standard). This provides better care, reduces staff burnout, and results in fewer ethical problems.

- Individual therapy is far more effective than group therapy, partly because most professionals that run group are not actually skilled in educating, room control, or handling a diverse set of people. Minimally, people should get one hour of therapy a week from a masters or doctorate level professional with a license (I’ll accept a masters level intern performing it if they are getting real supervision). The data is quite clear on this. Ideally, it is more than once a week.

- Even the worst program has a success story. It doesn’t tell us anything about the quality of the program. Data does. Very very few have any kind of data.

Most programs have unsatisfactory answers to these three questions. They try to make up for it by rolling their shitty programs in glitter; hence the glossy brochures, glimmering facilities, touching stories of success, and assurances from owners/workers that are in recovery. All that glitters isn’t gold – in fact, it’s probably covering up a lot of shit.

_______________________________________________________________

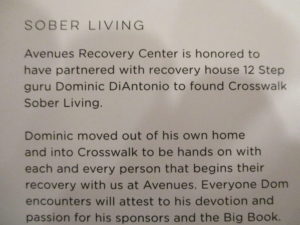

This is from a brochure that was given to me by a marketer that visited us at the Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies in January. We asked lots of questions, including the big three. I won’t go into what happened, because you could learn a lot by just calling them up and asking yourself. But their brochure had a statement in it that I haven’t come across before (Andrew Walsh pointed it out to me). The second and third lines celebrate the presence of a “12 Step guru” that helps the clients. It doesn’t state how much sobriety time the man has or if he has any education or credentials. I have never heard of anyone allowing themselves to be described as a 12-Step guru. The AA 12 and 12 book has a name for the guru types: bleeding deacons. From page 135: “At times, the A.A. landscape seems to be littered with bleeding forms.” In the same chapter, there is a stern warning against the professionalization of AA.

This is from a brochure that was given to me by a marketer that visited us at the Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies in January. We asked lots of questions, including the big three. I won’t go into what happened, because you could learn a lot by just calling them up and asking yourself. But their brochure had a statement in it that I haven’t come across before (Andrew Walsh pointed it out to me). The second and third lines celebrate the presence of a “12 Step guru” that helps the clients. It doesn’t state how much sobriety time the man has or if he has any education or credentials. I have never heard of anyone allowing themselves to be described as a 12-Step guru. The AA 12 and 12 book has a name for the guru types: bleeding deacons. From page 135: “At times, the A.A. landscape seems to be littered with bleeding forms.” In the same chapter, there is a stern warning against the professionalization of AA.

I am friends on Facebook with at least 32 people who have 20+ years of sobriety (I know a lot more than that though). None of them call themselves a guru or an AA expert. About a dozen of them work in the treatment field and do not advertise that they are in recovery; significantly, they have all been educated, trained, credentialed, and supervised (their expertise comes from that, not because they are in long-term recovery). Treatment programs continue to shock and amaze me.