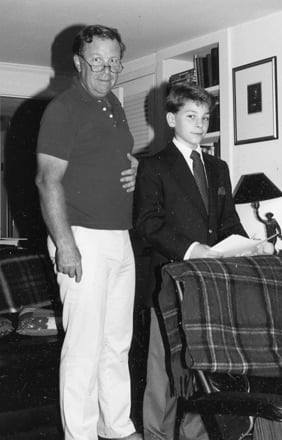

My father died a year ago today. November 19, 2021. We were snorkeling off Laughing Bird Caye National Park in Belize. He had a heart attack in the water. The guide brought him to shore. I arrived shortly after and took over CPR duties from some helpful strangers. I told him that I loved him and I wanted him to fight, but if he had to die, that I gave him permission to go. We gave him CPR on a speedboat as we motored towards the mainland. Upon our arrival, the doctor declared him dead. Within minutes, I thought about a 17 year old client who lost his State Trooper Dad to a 9/11 illness when he 12. I thought about four close friends who lost their fathers in their 20s. He was 82. I was 45. I thought about all the people I know with absent or shitty fathers. My dad was an exceptional man. Unsparing in his demands and criticisms of me growing up, for sure, but those forged me into who I am today. The last 15 years or so were spent as friends and equals; it was a wonderful relationship.

During a trip to Minnesota in the fall of 2018, I noticed my Dad was falling asleep while sitting down throughout the day. A week later, we were in DC and my uncle told him that he should see a cardiologist. My father was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. Scary, especially because his father, the original Frank Sr., had congestive heart failure and died of a heart attack in 1980. After his diagnosis, my Dad did three things that truly surprised me: he changed his diet, started to exercise regularly, and he took medication as prescribed from his doctors. That last one was a particular shock, as my Dad had polio and lived in an iron lung all throughout second grade. The doctors told him he would never walk again. He did and forever distrusted their advice afterwards, until the fall of 2018.

I sent a group text to about 15 of my friends. I told them what happened. That I had a lot to take care of, with phone calls and a police report and arranging cremation and figuring out how I would get his remains home. And that we were still on to hang out the day after I got home and what I needed most from them was not to be weird around me and, if they could, be prepared to tell me or write me stories about my Dad.

I made a bunch of phone calls within 2 hours of his death. I called his girlfriend, his brothers, my sister, and a few of his friends. I knew it was extremely important that each of them find out from a voice at the other end of a phone, rather than a text or email or newspaper clipping or social media post. Despite my sorrow, I had to deliver the news and explain what happened and let them know what he thought of them (in most cases) and what they might do to deal with their grief and remember him.

Immediately after his death and for a few weeks after, I kicked myself for taking him snorkeling. Hard. “What the fuck was the I thinking?” I’d say out loud when no one was around. The thoughts went like this, “If I hadn’t taken him snorkeling, he’d still be alive. I had caused his demise and was the source of my pain. Stupid!” But those thoughts were often counteracted with the following: “He chose to go snorkeling. It was the activity he wanted. He loved it, all his adult life. He was never one for sitting around or avoiding things because they were dangerous. I’m the same way. I’m going to drive fast and climb huge mountains right up to my end. It’s not my fault. And he wouldn’t want me to beat myself up over it. He died before his mind began to deteriorate. He died before his body failed him and robbed him of his oh so vital independence. He died in a beautiful setting doing something he loved and I was with him.” Those later thoughts won out, early and now. But, about once a month or so, I catch myself thinking about the snorkeling and curse myself and then have to walk myself out of it again. This is part of the grief process.

My grandmother died when I was 19. I spent the next six months getting drunk and high. I didn’t work much. I went to college in the fall but didn’t go to class. I didn’t exercise. In short, I didn’t do much of anything, other then get fucked up. I thought about how I wasn’t there at her end and how I was a screw up. Those constant thoughts and the ever stream of substances made the pain worse; crystallized it in amber. I got sober that winter and spent the next several years trying to process my grief. My regrets. The single best thing that came out of my grandmother’s death is that I vowed to a) not be a fuck up and b) make sure that I spent time with people that I loved and supported them in every way I could. In 2002, my friend Frazer overdosed. I was six and half years sober. I had spent the first few years of my recovery trying to get him clean. Every time he relapsed, I thought, “How could he do this to me?” and “Why can’t he just get this? He has so much going for him.” After a lot of sharing in AA meetings and therapy, I accepted that it wasn’t my fault. I couldn’t control Frazer’s addiction or manage his recovery. A little while later, I realized I was angry at him for dying. That sucked, being angry at my dead friend. Eventually, I got past that too. I decided to become a drug and alcohol counselor. To help people like Frazer. And to try to prevent their loved ones from suffering the pain that I had experienced.

My counseling career started in 2004. So many of my early clients had unresolved grief. Dead parents, dead friends, dead lovers, dead children. They had never talked about it with anyone. They lived with guilt and regret and anger and a powerful sadness. I listened to them. I got them to write about their loved one. I had them do things to honor the dead. At one point, I realized that while I had a lot of memories of Gram and Frazer, I didn’t have nearly as many as I thought I should. Immediately after their deaths, my mind was flooded with memories. Long forgotten ones. It was the emotions stirring up long dormant memories. I wish I had written them down. I told my clients to write about their loved ones for 30 days. “That shit is going to fuck me up Frank,” they usually said. “Good. It is supposed to. But let me be clear, you are going to be fucked up anyway. This gets it out. And then you can write about happy memories that make you laugh. That make you proud. We are going to work through all this guilt and regret.” And we did.

My friend Eric suddenly died in March of 2018. I was in a daze the first two weeks after he died. I could not believe it. I had a hard time sleeping. I was sad and angry and guilty and confused. A terrible place to be. I wrote about him every night at 1130 pm. For 35 days. Sometimes I wrote for 30 minutes, other times for two hours. It helped. At one point, I wrote a story that caused me to sob. Guttural cries of anguish with thick drool falling from my lips. Most stories made me laugh. I shared them on Facebook. And I emailed them to people without a Facebook account. The responses were amazing. Comforting. Reassuring. People told me that my writing helped them. And inspired some of them to write. I took the best of their stories and the best of mine and my Dad edited them and published “The Book of Eric” that fall.

So I wrote about my Dad. For somewhere between 50 and 60 days. The stories centered around my childhood and his exacting standards, my later teenage years and substance misuse and his struggles with my problem, early recovery and young adulthood and the change in our relationship, and the last fifteen years which were filled with love and laughter and adventures and fantastic advice and support. Hundreds of people read every post. People who knew him well read them. People who didn’t know him at all did too. The feedback was wonderful. Helpful. We collectively grieved, which is infinitely better than grieving in isolation.

All the previous major deaths in my life had prepared me for this one. Because of my grandmother, I spent so much time with my father over the last 25 years. Nothing was unsaid. He saw me in my full glory. Frazer’s death taught me to lean on friends and keep moving forward in life. Eric’s death proved to me the fantastical significance and power of writing.

My father’s apartment in Phillipsburg loomed large. It was crammed full of photographs and books and jam packed filing cabinets and 25 years worth of “New Yorkers.” Sorting through his stuff would be a Herculean task. I had the energy to write about my Dad and continue to work and engage in my life. I didn’t have the energy to sort through his stuff. Too time consuming, too brutal. My mom stepped up. They had been divorced 27 years at the time of his death, but they had remained friends and, sometime in the last ten years, actually became good friends. She sorted through all his things. Figured out what should be kept and what should be donated and what should be thrown out. I went by a few times with a bunch of friends to haul stuff away to be thrown out or donated. My Mom probably put in 200 hours. It is one of the very great acts of service anyone has ever done for me. I will be forever grateful to her for it.

In late January, I ran a four part grief group over eight weeks via Zoom. It was for people that I knew from childhood or Rutgers or AA or the Army or Prevention Links or some other aspect of my life. I did it as a way of honoring my Dad. An act of service. Each group lasted 90 minutes to two hours. People had to do writing for each group. We read and laughed and cried and supported each other.

In late February, I returned to Belize to collect my father’s ashes. There are only three doctors in the entire country that can perform an autopsy – it took three weeks before his was completed. I couldn’t wait in Belize that long, so I returned to NJ. The US Embassy helped me locate a funeral home and I had his body cremated. Both the funeral home and the Embassy offered to ship the ashes to NJ via Fed Ex, but I said to hell with that (one of my Dad’s lines). I would not risk his ashes getting lost. Getting to Belize was quite the journey. My plane sat on the tarmac for three hours. The custom line was two hours long. I called the car rental company and begged them to stay open and then I called the funeral home to see if they would allow me to come by late at night to collect my father. It all worked out. While in Belize, I rewatched “Lonesome Dove,” a Western that my father introduced me to. It is the story of two old Texas Rangers and their last adventures. Gus dies in Montana and asks his friend, Call, to take his body back to Texas. “Texas? We just got here. Now you want me to bring you back to Texas.” Gus replied, “Yes, Texas!” My father had laughed at that scene every time we watched it together. I felt like Call hauling my Dad’s ashes back to NJ. While I was in Belize, I ended up taking a yoga class for five mornings in a row. It was something I had done a bit several years earlier and had meant to continue, but my crazy work schedule and then deployment and then Covid had prevented me from doing so. The result of taking yoga in Belize is now it is back in my life. Sometimes two days a week, sometimes four. I feel great. Another gift from my father.

In March, we held a memorial service at Rutgers. Dad was an atheist. I could not hold a service for him at a church. I did not want to hold one at a funeral home. It was too cold to hold one outside, and I did not want to wait for spring. Dad was a professor at Minnesota and Colorado. He was a lifelong learner and teacher. Rutgers published his first book. Rutgers is my true home. Dean Lea Stewart secured the space for the service at the Art History building. Perfect. It was a four hour ceremony. There were daffodils. About a dozen people spoke. I read a few different stories between each speaker. I cried. I laughed. I exuded pride and gratitude. My Mom gave a performance for the ages, telling the story of his childhood and work life and how he was more loving to his girlfriends than he was to her, but it was ok, as she was happy he continued to evolve.

Throughout the spring and summer and fall, I thought about my father the most while biking. We took a lot of rides together on the D&R canal; sometimes in Phillipsburg, but usually outside of New Brunswick. Dad biked a lot, especially after his diagnosis. The one constant thought that comes to me while biking is this: “my father loved how I lived my life.” That’s incredibly comforting.

I also think about him when I am driving at night. I drive a lot. At least once a month to Albany for work, and more often for some long ass hike in the Catskills or Adirondacks or White Mountains. I used to call my Dad when I was driving late at night. Catch up on his activities, my work, the Vikings, and the latest American political shit show. He gave calming advice. I miss those late night talks the most, I think.

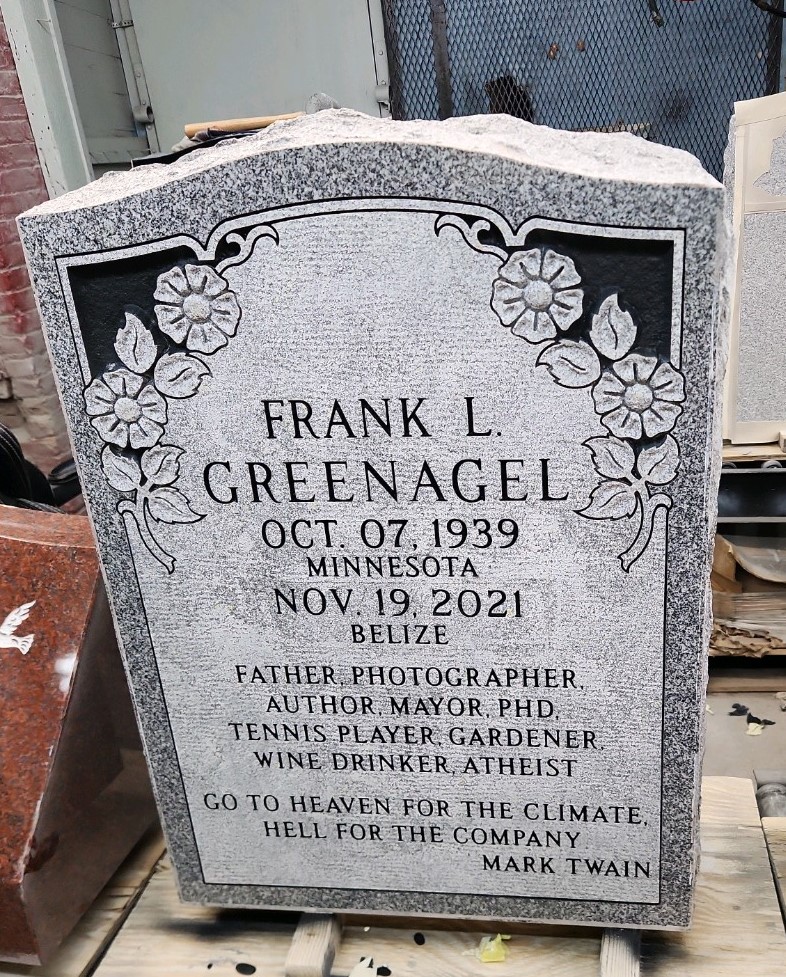

In the late summer, I had his tombstone made. I put a lot of thought into it. I wanted to capture his various roles and activities. And I wanted strangers to wander past it in the distant future and both wonder and laugh. To borrow from George W. Bush, Mission Accomplished, but for real.

In early November, Andrew Tortora, my college roommate of seven years, came by my house to “cut my father’s ashes like a brick of cocaine.” Andrew is not a drug dealer, but rather a gourmet chef and scientist. He makes OCD right corners and had the neatest notes in college I have ever seen. He brought a little scale and weighed out my father’s ashes. We put exactly half in a box that will go in a grave in Oldwick, NJ. The rest we divided up into several bags that I plan on scattering in places of vital importance. I said it then and I’ll say it again here, get yourself a friend that will cut up your father’s ashes without question or pause.

I’ve spent the last week in Arizona. On Veterans Day weekend, I hiked the Grand Canyon rim to rim to rim with some boon companions. I spread my father’s ashes in three different places: Coconino Overlook, just below the North Rim, on the banks of the Colorado River in the moonlight, and at Plateau Point at sunrise. I like the spots so much that I want some of my own ashes scattered there some day. Scattering his ashes was not a sad affair; it was imbued with love and respect and honor and devotion.

So here I am, here we are, one year later. For sure, I miss my Dad. But I never fell apart. Because I did the work. I wrote about him, talked about him, listened to stories about him, kept working, spent time with family and friends, exercised, and kept doing things I like doing (I hiked and biked and took yoga classes more than any other year and attended a ton of plays and ate a lot of steak and smoked a bunch of cigars). There was always something I had to look forward to doing to honor my Dad. Purposeful grieving. Actions with meaning. This is how I got through it. And why I am thriving today. Thanks for reading. And I hope that this helps some of you with your own grief journeys some day. Peace and love and remembrance. Ever Forward!