I love the US Army; I have joined it twice in my life. I enlisted in 1996, was honorably discharged in 2004 and then was directly commissioned in 2014. That does not mean that I like or approve of everything that it does or how it always goes about its business. My feelings for the Army are akin to the love one has for a family member but hopes that they make better choices (or how one can love a university but wish that their athletic program would just disappear into a black hole, never to return). All of that is preface to this: the Army has an alcohol problem and that problem has massive ramifications.

This summer, I reported for a month of medical officer training at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. There were 365 people in my class. There were about 40 prior service people (including some enormously impressive individuals), a ton of recent ROTC grads, several green-to-golds, a few West Pointers and a bunch of directly commissioned medical professionals. We were divided into six platoons; I was part of 3rd Platoon. While I got to know a number of my fellow soldiers, most of the people that I had in-depth conversations with were from the 3rd. I have been working in the addiction treatment and recovery support field for a dozen years, and yet I was still moved (not surprised) that more than half of them have a family member that either is in active addiction, is locked up because of their use, is currently in treatment somewhere, or died directly from alcoholism. When I told them what I do and that one of my goals is to help the military institute better policies for mental health and addiction treatment, every one of them said something to the effect of “bless you” or “can we clone you” or “what can I do to help?”

Throughout the training, multiple instructors and cadre would make references to drinking and a few would ask “how many margaritas did you drink this weekend?” to numerous soldiers. They meant well, and were trying to be free and easy and bond with their troops. I thought it improper though and that it sent the wrong message. I conferred with a few psychologists and a number of doctors about their reactions, and they expressed frustration and occasional exasperation about it as well. Here we are, 365 regimental medical officers, being trained in a variety of methods to help “preserve the fighting strength of the Army” and we were continually exposed to a drinking culture. To be clear, I’m not part of a temperance movement – most people can handle alcohol without a problem and have a right to drink. That said, I, along with a number of my highly educated peers, believed that it was improper and sent the wrong message.

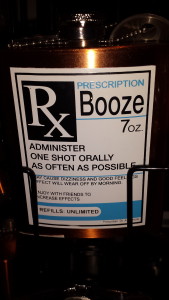

One Saturday, a group of us went to the AMEDD (Army Medical Deparment) museum. We learned about the history of Army medicine (as a New Jerseyan, I was happy to learn that Dorthea Dix was a Civil War nurse who also helped found early mental asylums) and how it has evolved over the course of time (I will write about this in the near future). It was educational and filled me with pride. Before we left, we stopped by the AMEDD museum store, where to my horror, the above pictured flasks were for sale. I was outraged – they should not be sold there. It’s a terrible message. I was most upset about the “RX Booze” labeled flask.

Alcohol misuse, abuse and dependence are problems within the military. Especially because there is a strong correlation between alcohol misuse and

(a) untreated PTSD

(b) sexual assaults

(c) suicides

These are areas that the Army (and military as a whole) has acknowledged as huge problems and need to be addressed (we were exposed to multiple sexual harassment and assault trainings). They do not happen in a vacuum though, and all three of those problems are exacerbated by alcohol. Getting leadership to talk less about weekend drinking and eliminating the sale of spring-breakish flasks will not fix these problems, but doing so will begin to change the alcohol-soaked culture that permeates throughout much of the Army. It starts at the top. To quote one of the cadre, “make it happen.”

One thought on “The Army’s Alcohol Problem”

Comments are closed.