*note: I wrote this in March of 2017 for a website that is now defunct. I stand by the sentiments herein. I have been thrilled with the police response to working with people with substance misuse disorders and the willingness of many departments to change their longstanding procedures. I believe that with proper recruitment, training, and supervision, the profession can continue to evolve and improve.

——————————————————————————

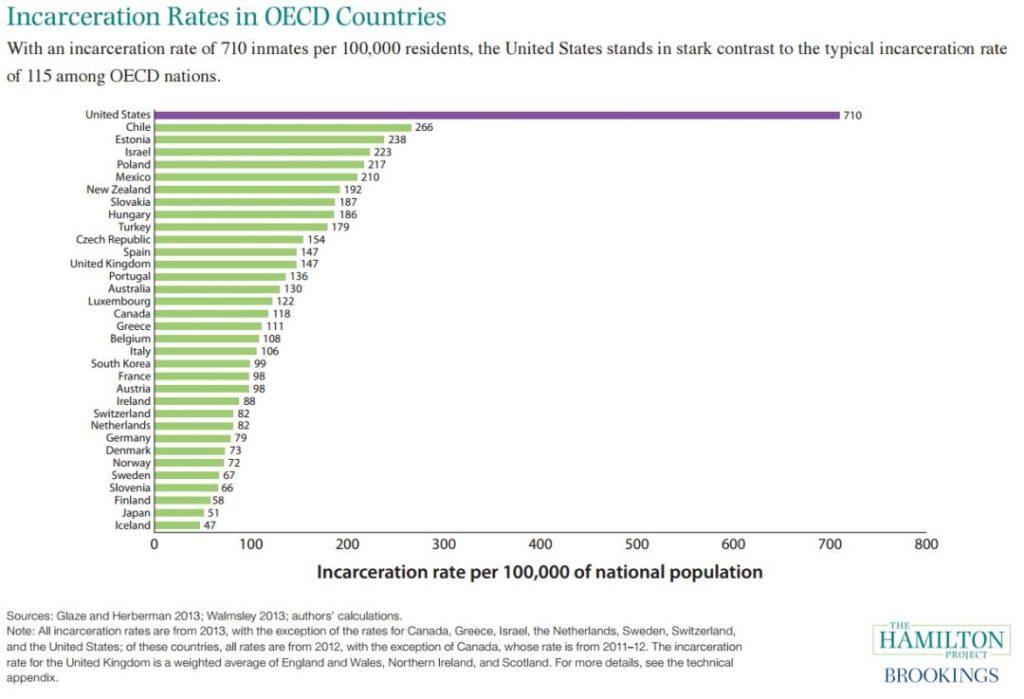

In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared the war on drugs. There was a brief respite under President Carter (who unsuccessfully called for the decriminaliziation of marijuana), and then President Ronald Reagan ratched up both the rhetoric and incarceration rates while also cutting funding for treatment. Presidents GWH Bush and Bill Clinton continued to spend billions trying to arrest away the drug problem. The roots of the modern opioid epidemic began during the Clinton and Bush II administrations with the aggressive marketing of pain killer by companies like Purdue Pharma. While incarceration rates have gone down the last few years, the United States continues to be, by far, the number one jailer in the world in both rates and total numbers.

The Vera Insitute of Justice estimates that the US spends about $75B a year on corrections, and this does not include capital building costs or pensions and benefits for corrections workers. For that money, over 66% of ex-offenders are arrested again within three years and almost 50% return to jail or prison within that same time. It has been a terrible return on the public dollar.

Despite the money spent on incarceration, drug overdose rates in America have increased from about 23,000 in 2002 to over 50,000 in 2015. Drug counselors, law enforcement, policy experts and politicians started sounding the alarm at the end of the last decade. The Massachucettes Bar convened a Task Force in 2008 and released a report. Other states and counties followed (I chaired the NJ Heroin and Opiate Task Force in 2012 – you can read our report here). Forward thinking governors began to pay attention, and both Democrats (Pete Shumlin –VT, Andrew Cuomo – NY) and Republicans (John Kasich – OH, Chris Christie – NJ) accepted the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion and instituted new policies to combat the epidemic (the implimentation of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs, Needle Exchange Programs).

I have trained thousands of law enforcement officers in multiple states (I’ve also provided counseling to many). Whenever I conduct a training, I ask them why they joined the force. While answers like “I was in the military and missed the uniform and comraderie” or “It’s a family business” or “It is a good job with benefits,” the most common answer has always been “to catch bad guys” or “to help my community.” Police have been the action arm in the failed war on drugs for decades. Not only has it not been effective, but it has burned out a few generations of cops. The drug war violated the rights of many Americans (dis-proportionally people of color) and it inflamed conflict and negative views between minority communities and the police.

After decades of arresting

millions of people for small possession,

law enforcement officers started to make changes on the local level.

Veteran police officers talked about how they had spent their careers busting

people for drug use and that the problem had only gotten worse. Other cops

stated that the focus on low level drug busts and arrest stats took the focus

away from more important crimes that required more work – burglaries, violence,

and sexual assaults. As drug overdose deaths continued to skyrocket this

decade, police officers began to carry Naloxone. Only a few departments used it

in 2012, but more and more added it to their basic equipment each year and now

it is standard in most departments throughout the nation. Police officers

administer naloxone to individuals who are overdosing more than any other

professional group.

While many veteran officers

support this change, young police officers often wonder “what is the point of

using Naloxone on a drug user?” Law enforcement officers occasionally express

frustration over administering Naloxone to the same individual several times

over the course of a few months, or reviving someone with a long criminal

history, or reversing an overdose of a person who has obviously been neglecting

their young children. This frustration stems from both a lack of training on

addiction and a overall macro level failure of public policy.

Naloxone was given to police

and first responders to reduce the number of overdose deaths. But there was no

initial follow up plan, so after a drug user was revived he was just sent on

his way. Over the last few years, a number of police departments (or county organizations)

have created programs to assist drug users after they have been revived. Over

the last three years, new programs (often called PAARI – Police Assistance

Addiction and Recovery Initiative) have sprung up around the country. Programs

like Angel in Gloucester, Massachucettes were set up to help heroin users get

into treatment instead of arresting them. Some programs have an embedded social

worker in the station (Arlington, Mass), while others hand out information

about treatment (START in Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, NJ), while others

take them to local hospitals and detoxes (Operation SAL in Camden County, NJ).

Most police departments have not developed a program yet to better handle the

people that they have revived. There are enough models that departments can

choose the one that best fits their department and municipality.

It is important that police

get training on this issue from someone that is knowledgeable about drug

treatment, state and federal policies, and also has a working knowledge about

law enforcement work and culture. In the last two years, there has been a

number of for-profit treatment programs that have attempted to train police and

set up relationships with departments in order to funnel clients with cadillac

insurance to their rehabs. Not even senior law enforcement leaders know the

difference between a non-profit program that uses modern data analysis and a

predatory for-profit program that has no interest in assisting indigent

clients.

The War on Drugs failed. Both

Democrats and Republicans have finally said so. Law enforcement knew it before

the polticians did. Now cops are the ones that have made the biggest change,

and they need proper training.