I have labored, really labored, to improve the lives and conditions of others for almost 20 years. There have been a great number of individual triumphs – lives turned around, families restored, jobs saved, and lessons taught. And yet, the 21st century has seen a fair share of horrors and 2020 has been utterly disastrous for so many people all over the world. When one takes a hard look around, it is easy to get frustrated. Exhausted. To even consider packing up and isolating in a forest on a mountain in order to avoid falling to despair. In good times and bad, I often seek solace and answers from literature.

In the prologue to the Wife of Bath’s tale in The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer offered up the following line that I often think about: “The wisest man minds his own business and does not worry about the conduct of the world.”

Because if you worry about the conduct of the world, you will be perpetually frustrated and often aghast. I can understand why someone would just want to retire to their library or garden or “sail away from the things of man” (this is a line from the terribly underappreciated Joe vs the Volcano).

Huckleberry Finn had enough of humanity to decide that he wanted to float away on a raft because civilization was terrible. Life on the raft with Jim was wonderful, and every time he went ashore he was yet again confronted with awful examples of human greed, racism, selfishness, anger, and violence. In the middle of Twain’s novel, Huck observed a group of townspeople tarring and feathering two con men and said, “Well, it made me sick to see it; and I was sorry for them poor pitiful rascals, it seemed like I couldn’t ever feel any hardness against them any more in the world. It was a dreadful thing to see. Human beings can be awful cruel to one another.” By the end of the novel, Huck’s alcoholic and physically abusive father is dead and Jim is freed, yet Huck decides to leave civilization anyway and make out for “the territory.”

Like Twain, Shakespeare despised the mob (not the Northern NJ Italian type) because they were rash and violent and fickle. At the start of Julius Caesar, the people are out in the streets celebrating Caesar’s latest triumph. Marullus and Flavius, two Senators, engage a few of them in conversation before Marullus chides them, “O you hard hearts, you cruel men of Rome, Knew you not Pompey?” Because they used to cheer and celebrate Pompey before he was defeated by Caesar. Throughout the play, Shakespeare does not take a stance for or against Caesar, but he clearly has great disdain for the quick turns that humans take and how easily they cheer other people’s destruction.

Throughout human history, religion has sought to temper these violent impulses and drive away the worst aspects of humanity while encouraging kindness, charity, and peace. In theory.

In the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, many of the absolute worst people who beat and murder slaves are “pious souls” and “devotional” and one is “a class leader in the Methodist church.” Not only has religion failed them, but it is used to prop up these heinous people. Some of them even use religion to justify their abhorrent behavior. His autobiography provides such a devastating indictment of American Christianity that Mr. Douglass felt the need to explain it in the appendix: “between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference – so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure and holy, is of the necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt and wicked.” While American Christianity (in all its many flavors) is far more enlightened in 2020 than it was in 1845, there is still a rampant hypocrisy that seeps out of churches throughout the land.

In the excellent show Good Omens (written by Neil Gaiman), there is a scene in episode three where an angel and a demon are watching the Crucifixion. The demon asks the angel what Jesus said that so offended those around him. “‘Be kind to each other,’” the angel informs him. “Yeah,” the demon replies, “that’ll do it.” It’s a funny and scathing moment.

As a student and now teacher, as a reader and now writer, as a therapist who engages in work on the micro, mezzo, and macro levels, I am continually reminded that people are amazing at pushing their perspectives and largely being unable to see other people’s sides. Most people that I talk with about culture, society, politics, work, religion, gender, race, sexuality, or class tend to lead with and focus on their experiences and their grievances, rather than listening to others. People love to tell others how to live. Again, I’ll cite Twain: “Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits. Fanatics will never learn that, though it be written in letters of gold across the sky.”

I got sober at 19 with the help of treatment and ongoing therapy and AA meeting attendance. AA was brilliant in that it had me focus on myself, my problems, my flaws, my behavior, my part, and what I could change. I was exposed to the the Prayer of St. Francis, which provides excellent advice:

Grant that I may

Not so much seek to be consoled as to console

To be understood, as to understand

To be loved, as to love

For it is in giving that we receive

And it’s in pardoning that we are pardoned

About ten years ago, I was counseling a student at Rutgers who was a finance major who had a job lined up with a Fortune 500 company. His plan was to spend a couple of years there and then to get his MBA so that he could return to Wall Street and acquire more power and make “some real money.” With that line, he summed up the true religion of modern America (go read Ayad Akhta’s Junk and then you and I can talk). I remember thinking about how there are some people that don’t deserve my help; I understand that few people will actually engage in meaningful work that improves the lives of others and leads to the betterment of society, but I think that people should at least follow the Hippocratic oath when looking for work: “Do no harm.” I wrestled with the notion of whether or not I should help someone who would profit off the work of others while contributing nothing to the world, and in fact, possible working on destabilizing the economy and getting rich while others have less and less. I ended up giving him the exact same attention and care that I would have anyone else.

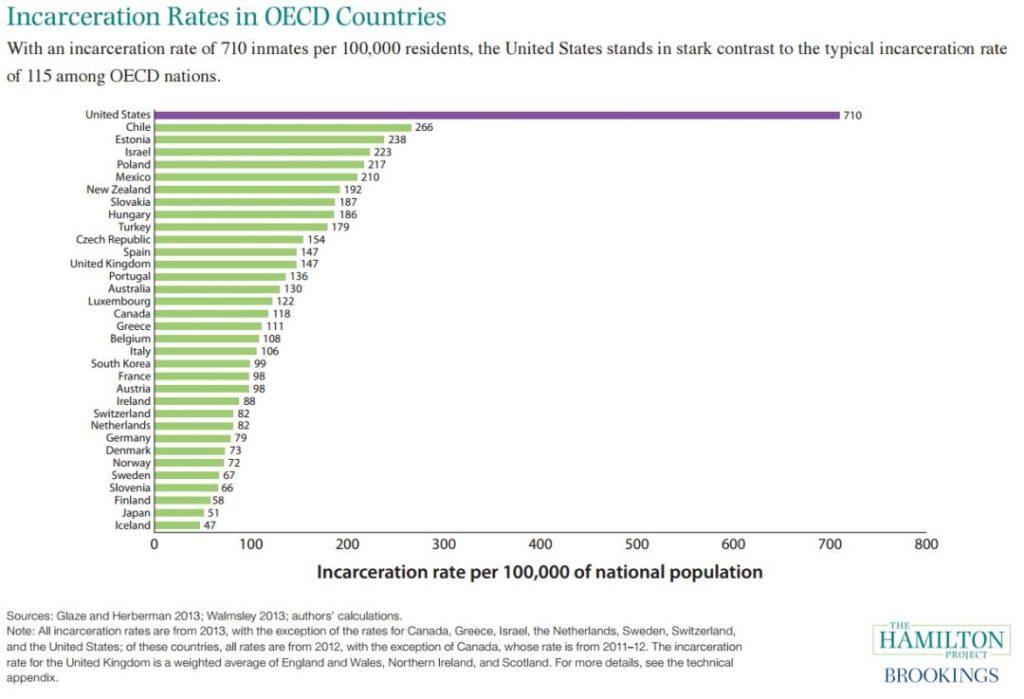

This piece isn’t written for everyone. In fact, it is for a minority of people. Those that are good and that are trying to better the lives of others. Not in theory, but in practice (years ago, I was friends with someone who had an astonishingly distorted view of himself. He thought he was a wonderful person, but he was incredibly selfish and argumentative and ended driving a lot of people, including myself, away). It is easy to be frustrated. At any time. But certainly now, in 2020. Not just with the pandemic or systemic racial injustices or economic disparities, but a litany of other problems too, including, most significantly, climate change.

Thoughts of giving up or quitting and sailing (or floating or hiking) away are normal. And rational. But these feelings and this debate are not new. J.D. Salinger wrote about it The Catcher in the Rye. Holden Caulfield was horrified with society. The book was published in 1951 and as a rich young white male, he was certainly in that era’s great winners’ circle. He had, in fact, been exposed to very little and was still thoroughly upset. Near the end of the novel, he meets up with a former teacher of his, who offers some wonderful advice that I also often lean on:

Among other things, you’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior. You’re by no means alone on that score, you’ll be excited and stimulated to know. Many, many men have been just as troubled morally and spiritually as you are right now. Happily, some of them kept records of their troubles. You’ll learn from them — if you want to. Just as someday, if you have something to offer, someone will learn something from you. It’s a beautiful reciprocal arrangement. And it isn’t educational. It’s history. It’s poetry.

Of course, the advice is muddied when that same teacher starts petting Holden on the head while he is sleeping. Holden wakes up and runs off, thus further alienated from people. Still, the advice is very good. It was a brutal stroke for Salinger to give that to the reader and then have the speaker attempt to molest the protagonist.

I am frustrated with people and Americans in particular (this has been a two decade thing, by the way). The news is upsetting, comments at the end of articles are often sickening, and the selfishness and conflict that seem to pervade so much of our modern world understandably urges me to throw up my hands and say “Enough with the lot of you” and leave the mess because, in Roger Water’s words, “it’s not easy, banging your heart against some mad bugger’s wall.”

Humanity is the mad bugger. Clearly.

And yet. I choose to stay. And work. And help. And hope. I am inspired by the work of others; by their effort, their care, their perseverance, their stories. It is possible to hold the conflicting thoughts that humanity is often terrible and yet I’m going to stick around and help them anyway. So, don’t give up. We keep trying til the very end. Just make sure you stop and smell the roses, walk among the lillies, watch the sunsets, and laugh a bit.